The Psychology of "Somewhat": Challenges for the Interpretation of Survey Data May 2014

Want more free featured content?

Subscribe to Insights in Brief

Measures from surveys of consumer attitudes, intentions, and behaviors continue to inform many marketing decisions, including strategic decisions about whom to target with messages, products, and services; associated tactical decisions (including media placement of messages); and anticipation of the future demand for products and services. Surveys are easy to administer over the internet, can reach representative samples of populations, and allow for quantitative analysis. Additionally, surveys are the focus of renewed or increasing interest from marketers, primarily because of their extension into the world of mobile technology, offering opportunities for nearly real-time feedback from customers.

At the same time, many marketing researchers and marketers are aware of the limitations of surveys. Surveys are often superficial (in comparison with depth interviews), biased because of the fallible mode of self-report (in comparison with direct measurement of behaviors), or incomplete because of coverage error (depending on the quality of the data provider). Although discussions of the limits and advantages of surveys in general are quite frequent (see also the Strategic Business Insights white paper "Garbage In, Garbage Out: Survey-Question Design"), little emphasis is typically on the specific ways in which the analysis of seemingly straightforward survey questions can lead organizations to draw profoundly misleading conclusions. In particular, the focus of the present paper is on the common practice of treating survey respondents who indicate full agreement with an issue as falling on the same continuum with respondents who express only partial agreement with an issue. As the analysis below shows, respondents who fully agree can represent qualitatively different markets than can respondents who partially agree with an issue or concept.

We examined this issue in a recent Strategic Business Insights (SBI) national probability survey of US adults about the topic of climate change, sponsored by ecoAmerica and its partner organizations (see American Climate Values 2014 at http://ecoamerica.org/research/). To assess overall belief in climate change, we asked the following question:

How convinced are you that climate change is happening?

- I'm not convinced at all (11% of Americans)

- I'm mostly not convinced (8% of Americans)

- I'm somewhat convinced (31% of Americans)

- I'm very convinced (40% of Americans)

- Don't know (10% of Americans)

As the percentages in parentheses indicate, the potential for positive action on climate in 2014 should be substantial, particularly when one combines the percentage of people who are "somewhat convinced" with the percentage of people who are "very convinced"—a common practice among survey analysts who wish to assess the full potential of an issue, product appeal, concept, or concern. Some 71% of Americans are either partially or fully convinced climate change is happening and presumably would be willing to take some form of action to mitigate the effects of damage from climate change or prepare for its consequences.

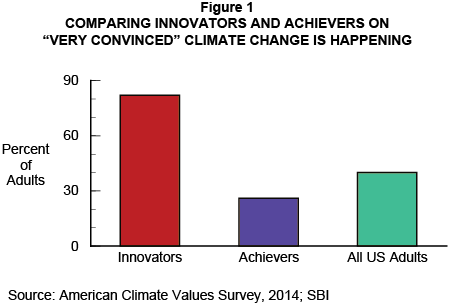

However, analysis using VALS™—SBI's consumer-insights tool—shows that this conclusion would be erroneous. Certain types of consumers strategically use the "somewhat convinced" option to appear open to an issue, while justifying inaction at the same time: They are qualitatively different consumers from those who are fully convinced. The distributions in Figure 1 compare the responses of VALS Innovators—some of the most forward-looking and climate-concerned citizens in the United States—with those of VALS Achievers, who are moderate, family-centered consumers living busy lives, prioritizing work and family obligations, and rejecting untested or inconvenient ideas until they are fully proved or become palatable for mass-market consumption.

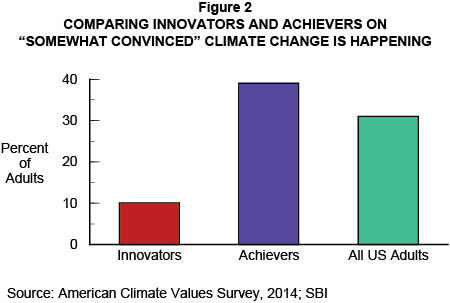

As Figure 1 shows, the vast majority (82%) of Innovators are "very convinced" climate change is happening, whereas only 26% of Achievers are—reflecting full concern significantly below market norm. The pattern reverses for "somewhat convinced" (see Figure 2), with Innovators dropping off to 10% and Achievers increasing to 39%. As an aside, Achievers are at market norm (10%) for admitting they "don't know." Not knowing is an overall less-popular response option than being "somewhat convinced" because of the negative perceptions that associate with being not knowledgeable.

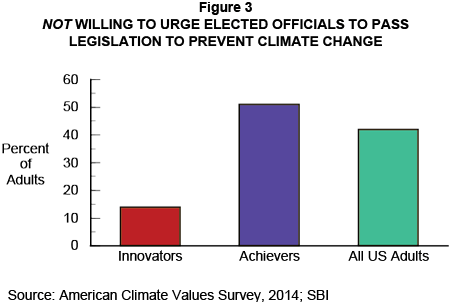

To combine "very convinced" and "somewhat convinced" options into a "net agree" measure is to mix apples and oranges—or two different "markets" about climate—with very different psychological profiles. For Innovators, being "very convinced" necessitates immediate action about climate. Unsurprisingly, many individuals active in the environmental movement are Innovators. For Achievers, by contrast, being "somewhat convinced" justifies inaction on the issue and maintenance of the status quo in which they are successfully operating. Figure 3 confirms this intuition.

The majority of Achievers (51%) are unwilling to urge elected officials to take action about climate change, whereas only a small minority of Innovators are unwilling to do so. The next largest proportion of Achievers (24%; not on Figure 3) are willing to act within the next 12 months—the psychological equivalent of "somewhat" acting. For environmental groups, this pattern of responses is disturbing. On the one hand, a large majority of Americans apparently acknowledge climate change is real (or somewhat real). On the other hand, few key groups are willing to take action about it. Achievers are a key group in driving the acceptance of new ideas, products, and services to a mass-market audience in US society, because of their role-model status for many other consumer groups. Achievers' partial agreement that climate change is happening is contributing to slow action about climate. Put differently: The relative isolation of true climate concern among Innovators is limiting progress on a larger-scale take-up of the climate movement.

Conclusion

Methodologically, the common practice of combining adjacent response categories on surveys can be vastly misleading. VALS provides a lens on identity and self-presentational motivations that sheds light on strategic survey-question responses among US consumers. Beyond analyzing survey responses, VALS facilitates a deeper discussion of consumer motivations that may help or hinder various initiatives. Achievers, who wish to be perceived as normal or moderate, often avoid extreme response options on surveys—just as they avoid adopting untested behaviors in the real world. On significant but uncomfortable issues, Achievers show opposition to demands that introduce subjectively unjustifiable costs or inconveniences (such as those associated with climate-change action) by "somewhat agreeing" with the issue or request. Subtly, being "somewhat convinced" delays almost all action until achievement of full epistemic certainty—which, in the case of Achievers about uncomfortable issues, maybe be very far in the future.

To learn more about using VALS to shed light on the motivations of your survey respondents, contact the VALS team.