Making Urban Environments Smart Featured Signal of Change: SoC913 December 2016

In February 2012, SoC561 — Urban Connectivity discussed how an interconnected web of infrastructures for intelligent communications, traffic systems, utilities, and waste disposal has the potential to create a completely new environment for innovation, energy efficiency, and economic efforts. Now, because of increasing interest in and developments relating to the Internet of Things (see, for instance, SoC809 — Industry 4.0)—including connectivity for an increasingly wide range of objects (see, for instance, P0883 — Object Connectivity), new transportation considerations in urban mobility (see, for instance, SoC907 — Public Transportation in Transition), and a better understanding of big-data applications and their limitations (see, for instance, SoC879 — Big Data: Working with Uncertainty)—smart-city initiatives are becoming a priority for urban planners, administrations, and infrastructure developers.

Urban planners, cities, and companies will have to find ways to adjust and utilize existing infrastructures.

No consensus about what smart cities and infrastructures actually are yet exists, and no best practices for planning for, implementing, and leveraging such environments have yet emerged; however, many smart-city initiatives have launched around the world, as the following examples illustrate. Recently, the city of Columbus, Ohio, won the Smart City Challenge (www.transportation.gov/smartcity) by the US Department of Transportation (DOT; Washington, DC), which pledged as much as $40 million to help the winning city completely integrate connected vehicles, driverless cars, and intelligent sensors into its transportation network. During the challenge, 78 cities submitted proposals, and the DOT chose 7 as finalists: Austin, Texas; Columbus, Ohio; Denver, Colorado; Kansas City, Missouri; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Portland, Oregon; and San Francisco, California. As part of its Smart Nation project, the government of Singapore plans to deploy sensor networks and cameras around the city-state to collect data about daily life. Launched toward the end of 2014, the Smart Nation project focuses on the holistic use of technology by government and the private sector to improve lives and create business opportunities. Most of the information the sensors and cameras collect will feed into an online platform that will help the government develop a better understanding of, for instance, how diseases spread and what crowd behavior might look like during a disaster. The government also intends to share some of the data with businesses. Because of its small size, financial clout, and tight government control, Singapore has a unique opportunity to advance the understanding of smart urban environments and will therefore build up competitive strength in the smart-technologies market. The government of Australia has inaugurated the Smart Cities and Suburbs Program to "support local governments to fast-track innovative technology solutions that improve long-standing urban problems" (https://cities.dpmc.gov.au/smart-cities-program). In September 2016, the government used a series of roundtables in several Australian cities to elicit input about designing the program to meet the needs of local communities and governments. The Smart Cities and Suburbs Program could be of particular interest to observers, because Australia is a very city-centered country in which states are mainly dominated by their largest city. For instance, New South Wales has 7.5 million inhabitants, and about 5 million of them live in the capital city of Sydney; Victoria has 6 million inhabitants, and more than 4.5 million of them live in the capital city of Melbourne. Together, Melbourne and Sydney account for nearly 40% of the entire population of Australia.

Some regions already have significant experience with smart-city projects. For example, Amsterdam in the Netherlands has been running the Amsterdam Smart City (https://amsterdamsmartcity.com) initiative since 2009. The initiative focuses on six themes: Circular City; Citizens & Living; Energy, Water & Waste; Governance & Education; Infrastructure & Technology; and Mobility. Although the initiative commenced more than five years ago, City of Amsterdam chief technology officer Ger Baron admits, "I can give you the nice stories that we're doing great stuff with data and information, but we're very much at a starting point" ("Data-Driven City Management," MIT Sloan Management Review, 19 May 2016; online). This MIT Sloan Management Review study found some crucial lessons about the elements that are necessary to launch smart-city initiatives. For instance, nongovernment institutions play massively important roles in such efforts. The study highlights that data from the private sector is crucial to changing policies and that feedback and suggestions from citizens help smart-city initiatives succeed. The study also provides insights about the role of government in smart-city initiatives. Before beginning a smart-city initiative, cities should analyze and make use of the information in existing databases. And cities' experimenting with, learning from, and building incrementally on pilot projects can produce positive results. Cities also need to be aware that a smart city requires a chief technology officer, and they must manage expectations, because rapid change is usually elusive.

The smart-cities concept attracts a large number of infrastructure providers such as General Electric (Boston, Massachusetts) and Siemens (Berlin and Munich, Germany) that aim to develop products, services, and business models to address the emerging market needs. The developing market also attracts players in submarkets that focus on specific aspects of smart-city environments. For example, water companies in Germany hope they can leverage the country's expertise in Industry 4.0 to innovate the water business. The German Water Partnership (Berlin, Germany) is a network of 350 companies and research institutes, and its managing director, Michael Prange, believes that so-called Water 4.0 could create new export opportunities for Germany. Similarly, telecommunications-equipment provider Huawei Technologies Co. (Shenzhen, China) is exploring opportunities in smart sewage management in the Australian state of Victoria. Other companies see smart-city initiatives as a springboard to leverage their existing core competencies (data analytics, for example) to enter a completely new business field. In 2015, Alphabet (Mountain View, California) founded Sidewalk Labs (www.sidewalklabs.com), which aims to develop an integrated urban-innovation platform and multiple applications capable of speeding up innovation in the world's cities. During a February 2017 speech, Sidewalk Labs CEO Daniel Doctoroff indicated his interest in taking a fresh look at urban environments: "What would you do if you could actually create a city from scratch.... How would you think about the technological foundations?" ("Alphabet's Next Big Thing: Building a 'Smart' City," Wall Street Journal, 27 April 2016; online).

Indeed, what would urban planners do if they could create a city from scratch? Realistically, urban planners, cities, and companies will have to find ways to adjust and utilize existing infrastructures to make current urban environments smart, which is much more challenging than is creating a smart city from the ground up. The coming years will likely see a host of companies and even entire industries in competition to secure a sustainable and defendable market position.

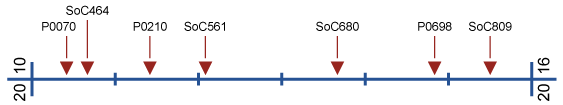

The Development of this Signal of Change

Data Points

- SC-2016-10-05-021

A recent MIT Sloan Management Review study found some crucial lessons about the elements that are necessary to launch smart-city initiatives. - SC-2016-09-07-057

Water companies in Germany hope they can leverage the country's expertise in Industry 4.0 to innovate the water business. - SC-2016-10-05-013

In 2015, Alphabet founded Sidewalk Labs, which aims to develop an integrated urban-innovation platform and multiple applications capable of speeding up innovation in the world's cities.

Implications

Making Urban Environments Smart

Smart-city initiatives are becoming a priority for urban planners, administrations, and infrastructure developers.

Previous Alerts

- P0070 — Designing Intelligent Urban Ecosystems (June 2010)

New concepts and approaches can limit human impact on the environment and allow people to use available resources in urban regions better. - SoC464 — Connected Cities (September 2010)

Ubiquitous connectivity will prove to be essential for the design of sustainable and productive cities and will provide the infrastructure for a more systematic response to mobility, capacity, environmental management, and other needs than has been possible in the past. - P0210 — Managing Urban Decline (June 2011)

Shrinking cities have become a topic on the urban-planning agenda in many countries, and managing associated problem areas is becoming a priority in many locations. - SoC561 — Urban Connectivity (February 2012)

An interconnected web of infrastructures for intelligent communications, traffic systems, utilities, and waste disposal has the potential to establish a completely new environment for innovation, energy efficiency, and economic efforts. - SoC680 — An Intelligent Robotic Internet (September 2013)

In the future, smart infrastructure, cloud-controlled robots, and machine-learning algorithms could turn pockets of the internet into intelligent systems that can sense, analyze, and take complex actions in the real world. - P0698 — Transportation Interconnectivity (November 2014)

New approaches that combine transportation alternatives and seamlessly integrate them into urban environments promise new mobility concepts. - SoC809 — Industry 4.0 (July 2015)

Advances in the Internet of Things, big data, and cloud computing are creating opportunities to advance manufacturing.