Consumers' Malleable Perceptions Featured Signal of Change: SoC975 November 2017

Consumers rely on a continuous stream of perceptions when making judgments about people and products. Ways to affect such perceptions exist. Ultimately, organizations may benefit from defining consumers' perceptions in malleable terms, and they may benefit from engineering environments and objects to generate favorable perceptions.

The effects of consumers' perceptions can seem counterintuitive to observers and marketers.

The effects of consumers' perceptions can seem counterintuitive to observers and marketers. In 2014, researchers from Southern Methodist University (Dallas, Texas) and the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada) examined rejection in a retail context. Their studies found that in a luxury setting, consumers who aspire to own a brand that is technically out of their reach like the brand more if they feel rejected by store employees than they do if store employees treat them kindly. This finding suggests that retailers' near-ubiquitous efforts to create friendly, welcoming environments for all consumers can be counterproductive; however, determining on the spot which consumers should be targets for rejection can be difficult or impossible for employees. Related considerations play a role in retail settings, and social psychologists have begun to conduct research about smiling that has revealed several empirical generalizations. For example, a distinction exists between full smiles and slight smiles. Studies suggest that full smiles signal warmth and friendliness but little competence, whereas slight smiles signal more competence but less friendliness. Salespeople who are in technical fields might want to employ slight smiles to maintain impressions of competence. Salespeople for events and other experiential services may want to employ full smiles. Several additional commercial implications exist for sales, product returns, job interviews, customer service, and general impression management. For example, companies with strict rules for product returns may want to train employees to employ full smiles to project warmth and minimize consumer frustration.

In the domain of advertising, changing consumer perceptions requires advertising agencies, social-media organizations, and anyone who markets directly to consumers to hit a moving target. A recent study by professors from Northwestern University (Evanston, Illinois) and Seattle University (Seattle, Washington) indicates that the perception that people distrust advertising across the board is false. The professors surveyed 400 people about 20 tactics commonly in use in both digital and television advertising and found that respondents had favorable opinions about 13 of the tactics. Participants had particularly positive reactions to advertising tactics such as highlighting positive reviews from consumer-review platforms from companies such as Amazon.com (Seattle, Washington) and Yelp (San Francisco, California) and rankings from third-party evaluators such as US News & World Report (Washington, DC). However, tactics such as "using paid actors instead of real people, or even hiring celebrity endorsers to express their affinity for a product, came off as 'deceptive' or 'manipulative,' according to those surveyed" ("Consumers May Be More Trusting of Ads Than Marketers Think," New York Times, 30 July 2017; online). Various advertising executives comment that brands need to prove their value rather than sell it and that authenticity is key. Currently, no hard-and-fast rules about what works exist. Persuasion techniques that may have worked two years ago—for example, retargeting consumers with products on Facebook's (Menlo Park, California) social network and making advertisements look like journalism on social media—may not be effective today. Strategic Business Insights' consumer research shows that individual types of people trust different sources of advertising, but the above study does not disaggregate by demographics or psychographics. The lesson here appears to be that advertising consistently coevolves with consumer knowledge, needs, and expectations. Some consumers attach strong perceptions—and corresponding evaluative judgments—to the legal category a business operates under. For example, researchers from the University of Texas at San Antonio (San Antonio, Texas) and the Pennsylvania State University (University Park, Pennsylvania) show that people's perceptions of for-profit social ventures—companies that have a social mission while pursuing profits on the side—are less favorable than are people's perceptions of nonprofit organizations. Consumers take any mention of a profit motive very seriously, equating it with greed. People appear to judge for-profit social ventures such as Alter Eco (San Francisco, California)—an organic-food distributor that helps small farming operations implement fair-trade and organic practices—primarily on the profit side of the equation. The researchers admit that their findings obtain because many people conduct minimal independent research into the finances and performance of organizations to understand how much money the organizations use effectively for the social cause they are pursuing.

An emerging area of research addresses the multitude of perceptions consumers have when they interact with products, packaging, and various other design elements. During six empirical studies, researchers from Boston College (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts) demonstrated a surprising relationship between the color saturation of objects and the perception of the size of objects: The higher the color saturation of an object, the larger people perceive the object to be; the lower the saturation of an object, the smaller people perceive the object to be. The researchers demonstrate several additional findings. For example, when shoppers intend to purchase products in large sizes, higher color saturation of the products' packaging results in shoppers' higher willingness to pay. This research can shed light on design principles for rooms, products, and packaging; can help architects and artists make more informed aesthetic decisions; and can influence the general execution of sensory manipulation in computer games and various user interfaces. Related packaging considerations exist. Researchers from Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) and the University of Kentucky (Lexington, Kentucky) examined how the shapes of product packages that remind consumers about idealized body shapes can affect consumer spending. In Western societies, thinness stereotypically represents hard work, restraint, and responsibility. During their studies, the researchers found that subtle reminders of this ideal body shape—for example, a beverage container with a shape reminiscent of that of a thin human—can cause overweight people to experience low self-efficacy. Feelings of low self-efficacy can undermine a person's ability to control his or her spending impulses, resulting in the person's making more indulgent shopping decisions. The researchers' studies revealed that overweight consumers indulged more when they encountered a thin humanlike container than they did when they encountered a wide container. This research suggests that simply implying a humanlike quality in the environment results in the activation of powerful comparison mechanisms.

The Development of this Signal of Change

Data Points

- SC-2017-10-04-029

In a luxury setting, consumers who aspire to own a brand that is technically out of their reach like the brand more if they feel rejected by store employees than they do if store employees treat them kindly. - SC-2017-10-04-072

When shoppers intend to purchase products in large sizes, higher color saturation of the products' packaging results in shoppers' higher willingness to pay. - SC-2017-10-04-075

The shapes of product packages that remind consumers about idealized body shapes can affect consumer spending.

Implications

Consumers' Malleable Perceptions

Organizations may benefit from defining consumers' perceptions in malleable terms.

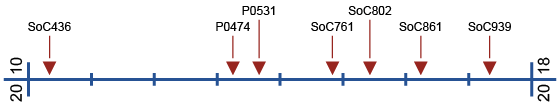

Previous Alerts

- SoC436 — Controlling Brands' Use and Exposure (May 2010)

Companies are ramping up efforts to ensure that their brands reflect companies'—and individuals'—intentions in a sea of social media and a proliferation of communication technologies. - P0474 — Balancing Luxury and Frugality (April 2013)

Companies face the tricky task of appealing to consumers' cost-conscious and luxury-loving sides simultaneously. - P0531 — Controlling Brands (September 2013)

Ensuring the right level of transparency, projecting honesty, and exerting the right level of brand control are all critical. Companies need to proceed carefully. - SoC761 — Brandless Futures? (November 2014)

Is a strong, recognizable brand still a prerequisite for success in today's fast-moving world? - SoC802 — Navigating Outside Influences on Brands (June 2015)

Branding options are becoming more difficult to navigate in the age of increasing consumer knowledge and participation. - SoC861 — About Subtle Nudges and Blunt Shoves (April 2016)

Behavioural Insights Team has offered to help governments address challenges such as fighting obesity, improving social mobility, and curbing extremism. - SoC939 — Dynamics in Judgment and Authority (May 2017)

This Signal of Change looks at influences on judgment and authority.