Culture and Global Marketing May 2012

In an era when most new growth is likely to come from developing economies (for example, China, Russia, India, Brazil, Indonesia, and the African countries), an important question for multinational firms continues to be how best to integrate country-specific cultural information into their international marketing strategy. Strategic Business Insights' global consumer research shows that consumer societies share fundamental underlying motives for consumption, suggesting on the surface that global streamlining of brands and products is possible across cultures. However, our research also finds that the specific expression of these motives varies significantly from culture to culture. Ultimately, our research shows that successful international marketing depends both on the correct application of general marketing principles and on a grounding of those principles in culturally expressed motivations that affect the flow of goods, services, and communications in each country.

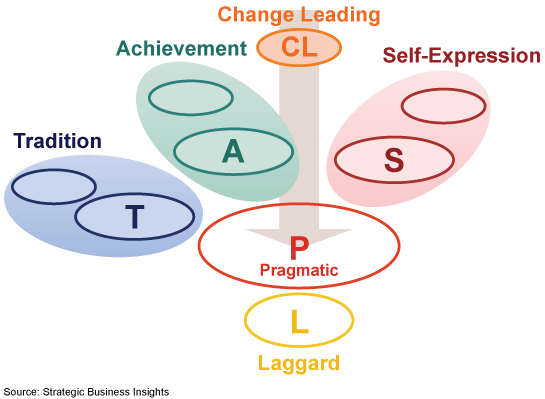

The above diagram shows in generic terms the major contrasts in consumer groups in cultures around the world. The contrasts exist along two dimensions: resources (vertical contrasts) and motivation (horizontal contrasts). Vertically, societies generally contain change-leading segments whose members enjoy the highest levels of prestige, mostly because they have access to significant financial and educational resources. These elite segments may lead societies in a variety of ways—for example, by exposing the culture to different ways of doing things, through new business ventures, or by leading in political roles. High-prestige consumers travel extensively outside their home country, are heavy consumers of media, and show strong intellectual interests. Societies globally also contain pragmatic and laggard segments. Pragmatic consumers are lower-income segments in a society— they have less access to material and educational resources. Change-leading and pragmatic consumers are relative designations within a culture and depend on the overall level of resources within a culture and on the degree of income disparities. A person at the bottom of the income ladder in the United States (for example, earning $700 a month) would be rich in many developing economies, such as Brazil. Similarly, having living-room furniture carries high prestige in the Dominican Republic, one of the poorest countries in the world, but is mundane in much of the developed world.

Across cultures, pragmatic consumers have similar attitudinal and behavioral profiles. Many pragmatic consumers have high expectations about the quality of the few products they buy, even if the products must necessarily have a low price point. Members of these consumer segments simply cannot afford to waste resources on products that don't work. They also tend to watch significant amounts of television (for example, soap operas), enjoy talking to their neighbors, and show interest in many topics, including religion, current events, sports teams, and local politics. Many companies anticipate continued growth from pragmatic segments internationally in the next decade, and many consumer-packaged-goods firms, such as Unilever and Procter & Gamble, have already made significant inroads among pragmatic consumers.

Interestingly, international marketers often lump pragmatic and laggard segments—the third and lowest-resource category on the vertical dimension—into a single low-income segment. Similar to pragmatics, laggards have few resources but additionally lack the attitudinal profile of interest in domestic, political, and sports topics, making them much less attractive than pragmatics to multinational companies.

In addition to considering levels of resources from an international perspective, one might also usefully recognize three powerful motivational orientations in most consumer cultures (the horizontal contrasts): Tradition, Achievement, and Self-Expression.

Across societies, tradition-oriented consumers value and preserve whatever has stood the test of time. They are motivated by principles, ideals, and beliefs that supply a society's code of ethics and social norms that regulate the distribution of wealth and opportunity. Tradition-oriented consumers can provide balance by providing counterpoints to fast-paced innovations that could potentially harm citizens of a country. Tradition-oriented consumers usually advocate reversing societal developments to an earlier time in history; from a marketing perspective, nostalgic appeals may work particularly well here, but the strategy of invoking tradition is not without risk. Similar to definitions of resources, definitions of traditional values, beliefs, and practices can vary significantly between cultures. In the United States, for example, traditional values often center on making responsible consumer choices based on certain principles, such as not wasting money or being informed (the value of information is traditional in US society). In emerging economies, such as Nigeria, tradition-oriented consumers are often preservers of the oral histories of the culture (information is packaged in stories) and maintain the artisanal skills of the past, such as the making of clay pots to store and preserve foods. Importantly, not everyone has authority to use the symbols of the past. Companies like Nike and Toyota have in recent years encountered surprising resistance to several of their advertisements in mainland China that featured traditional cultural symbols (lion statues, dragons, ancestral spirits, and Zen masters) alongside various outsider stimuli, including the brands, American star athletes, and the actual products. Tradition-oriented Chinese consumers heavily criticized the ads because traditional Chinese symbolism is sacred to them and cannot simply be used by anyone.

Achievement-oriented consumers often represent the aspirational "middle" of a society. They wish to advance their relative position in society, emulating the power elites that make up the change-leading segments. The consumer attitudinal profile of Achievement-oriented consumers can be bright or subdued, depending on their level of resources. Brightly aspirational consumers across cultures often have lower resources and simply wish to own the material belongings of the rich (for example, they wish to live like a celebrity). Higher-resource Achievement-oriented consumers often show subdued opinions as an adaptation to the need to change one's beliefs and values depending on whom one is talking to—typically to move ahead and build a social network (to be many things to many people). Achievement-oriented consumers push a society forward through the powering of production functions. The personal goals set by Achievement-oriented consumers often drive toward professional and educational achievements that may be hard earned given the societal power structures. Many Achievement-oriented consumers in developing economies are women whose goal is to step outside the shadows of their husbands, requiring a careful navigation of the male-dominated power structures (Nigeria is a case in point here). The United States in the 1960s represents a cultural example of these constraints for women in developing economies.

Finally, every society contains self-expressive consumers who seek excitement, stimulation and self-discovery. This motivation drives markets that center on consumption—in particular, entertainment media, recreational activities, fashion, sport, and leisure travel. Example behaviors that are explained by self-expression internationally are disco or nightclub attendance, frequenting of cyber cafés, and attendance at select sports events and stadium concerts. In the United States and Japan, self-expression accents novelty and being unique or even antiauthority, whereas in many Latin American cultures, such as the Dominican Republic, self-expression equates most with action—movement from experience to experience.

Companies wishing to leverage these major consumer contrasts in their global marketing efforts would do well to know that the expression of these consumer contrasts varies from culture to culture in terms of both what defines behaviors typical of the various groups and how intensely the motivations have expression within a culture. In highly fragmented and modern markets (such as the United States and Japan), high self-expression can show itself in extreme ways. For instance, younger people (younger than age 35) in the United States and Japan have higher stimulation scores (based on group mean difference) than have younger people in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. Consequently, the motivation intensity requires equally strong execution, which explains why US advertising that targets a high self-expression target is always outrageous and unconventional.

Finally, the relationship between the contrasts can vary depending on the culture. Tradition does not always provide a counterpoint to self-expression, for example. Latin American cultures contain segments that are high in self-expression (stimulation seeking) and high in tradition, resulting in lifestyles in which people blend excitement with traditional values.