Do Consumers Want Driverless Cars? October 2014

Want more free featured content?

Subscribe to Insights in Brief

Most major automakers—and, of course, Google—are pushing forward with a variety of driverless-car efforts. The US National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) describes four levels of autonomy. Progress is notable on Levels 1 (Function-Specific Automation) and 2 (Combined-Function Automation). Technical challenges abound with Levels 3 (Limited Self-Driving Capabilities) and 4 (Fully Self-Driving Automation), but they are the research and development goals for many players in the autonomous space.

Given all the excitement in the automobile industry, a big question is, Do consumers want self-driving vehicles? Associated questions include, Will they be able to afford them? Will there be strong consumer demand for certain autonomous functions and only minimal demand for others? To what extent will consumers replace their traditional cars with driverless ones and in what time frame? Will driverless cars be as common as traditionally owned second cars? Or will new business models take hold and make driverless cars mostly on-demand options?

Strategic Business Insights' VALS™'s recent research into Americans' attitudes about their cars offers insight into how the diffusion of driverless cars in consumer markets might play out. For example, nearly 24% of US adults indicate that they are OK with giving up control in a car if doing so would prevent a collision. The most innovative Americans (VALS Innovators) were more enthusiastic than average: Some 35% of them approved of the idea, as did younger self-expressive consumers (VALS Experiencers). Less popular with Americans was the idea of a car that could automatically take control from the driver and park itself. Only 17% of US adults overall thought self-parking was desirable. But VALS Innovators as well as the same self-expressive Experiencers segment were considerably more enthusiastic about this capability. More than a quarter of each of these groups agreed that they'd like a self-parking car.

Most people have difficulty in imagining what it would be like to use a product or service that no one has invented yet, so it's not surprising that only 15% of US adults said they wanted to ride in a driverless car. Most people need not only to see a new product but also to see other people whom they know or respect buy and use it. The more expensive the new item, the longer the adoption process generally takes. But most people are not all people, and characteristically, Innovators and self-expressive Experiencers—about 20% of all US adults—are considerably more interested in a driverless ride than are other Americans. They are also much more practiced in thinking about the future and imagining themselves living in it with new functionalities. Nearly a fifth of each of these two groups say they see obvious benefits to driverless versus traditional cars.

Driverless benefits likely to appeal to Innovators include the ability to use "drive time" in more interesting or productive ways, such as in reading a book, doing an information search, or watching a movie. Innovators are likely to appreciate the safety aspects of autonomous cars both for themselves and for society at large, including the likely drastic reduction in vehicle-related accidents and associated injuries, medical bills, deaths, and mortuary costs. Reducing driving fatigue and increasing comfort are likely Innovators benefits. Innovators will also be interested in the way autonomous vehicles extend the ability of older people to "drive" and maintain their independence. Experiencers will be attracted to the novelty of the concept—driving with no hands! And they may be attracted to driverless vehicles for some of the same Innovators reasons, including using drive time in more interesting (and likely more entertaining) ways and increasing driving comfort. The safety benefit is less likely to resonate with Experiencers, because they tend to feel quite immortal and much prefer speed over safety.

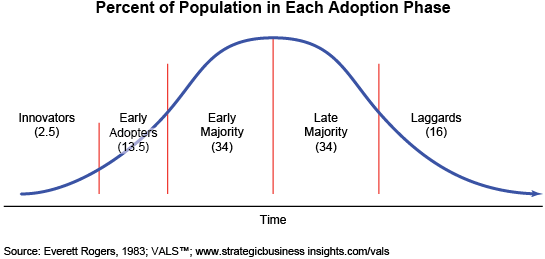

Everett Rogers, scholar and author, popularized the idea that when product manufacturers introduce innovative consumer products to the market, they go through several stages of adoption before reaching a mass market. He posited that truly new, breakthrough products are tried first by tiny percentages of innovative people. Later, other consumers—early adopters—may become interested and expand the new market somewhat. Products don't reach mass-market status until the early-majority users start buying. Reaching that stage requires, as Geoffrey Moore—author, speaker, and advisor about disruptive markets—descriptively put it, crossing a chasm of resistance.

Because both VALS Innovators and Experiencers expressed considerably more enthusiasm for driverless cars than all the rest of America, one might think that both these types of people would make up the innovators and early adopters of Rogers' scheme. But if a traditional model for car buying holds steady and people in the future continue to buy their own cars rather than rent, share, or participate in some other on-demand model, the people in Rogers' innovator-adoption stage will likely be VALS Innovators and not the self-expressive Experiencers. VALS Innovators have much higher disposable incomes than Experiencers do and so are more likely to be able to afford cars based on new, more expensive technology. Additionally, early in the development of the driverless market, consumers will likely buy driverless cars as second cars for use in special circumstances. Innovators are much more likely to own two or more vehicles today than Experiencers are.

However, if car manufacturers introduce Level 3 and 4 driverless cars via alternative car-sharing models in which consumers use and pay for just what they use—without the need for the large down payments, loans, insurance costs, and maintenance fees necessary for traditional car ownership—the open-minded but financially constrained self-expressive Experiencers might be part of the innovator and early-adopter mix along with VALS Innovators.

American consumers are not clamoring for driverless cars today. And a multitude of forces are at play about whether, when, and how Level 3 and 4 driverless cars will appear commercially. But when and if they do, the car manufacturers, the Googles, and others who make them available to the market will benefit from considering the kinds of people who will make up their initial innovator and early-adopter audience and why (What features and benefits appeal to them?) as well as later audiences that may buy as time progresses, prices come down, and driverless cars become more familiar.

To learn more, contact us.