Friend or Foe? Smartphones and Consumer Control March 2015

Want more free featured content?

Subscribe to Insights in Brief

With the nearly ubiquitous diffusion of smartphones in many societies, concerns about the negative effects of using these devices are becoming more prominent. Whereas some of these concerns center on data security and privacy issues, others are beginning to involve potential negative psychological consequences of using smartphones. (Strategic Business Insights' [SBI's] Scan™ covers this issue in P0595 — Connectivity Concerns and in SoC741 — Metadata and the End of Anonymity.) In 2008, China classified internet addiction as a bona fide disease and began sending teenagers into military-style boot camps, according to a Quartz report. Similarly, Patricia Greenfield, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and senior author of a study about the use of digital media, says that young people may be losing the ability to read emotions through facial cues, because of their relative overreliance on technology to communicate, and technology often lacks such interaction cues. On a more benign scale, some consumers are beginning voluntarily to seek rest from their mobile devices. Examples include the development of dedicated iPhone accessories that limit device use and Wi-Fi cold spots, such as Vancouver's (Canada) Faraday Café.

These dynamics outline an important friction area in smartphone use that simultaneously involves consumer—and overall societal—well-being, potential consumer resistance to continuous connectivity, mobile advertising, and many other aspects of a phone's user experience. Implications also exist for various business models, including those that focus on enabling deliberate rest from mobile devices. To shed some light on these emerging dynamics, SBI researchers surveyed—between August and November 2014—1621 smartphone users who voluntarily sought classification into one of SBI's VALS™ consumer insights groups. After receiving their VALS types, these respondents answered several questions about their attitudes toward mobile devices and 13 questions measuring their level of dispositional mindfulness. Mindfulness, according to Eastern traditions, is often associated with meditation and intense focus. The present measure of mindfulness, developed by Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer, represents a more Western view and simply involves interest in actively noticing new developments and behavioral flexibility—doing tasks differently. For example, people who score high on Langer's Mindfulness Scale tend to agree with statements such as "I'm always open to new ways of doing things," "I am very creative," "I attend to the 'Big Picture,'" and "I like to be challenged intellectually." From a mindfulness perspective, technology is neither inherently good nor inherently bad. Rather, technology may have negative effects to the extent that users fall into rigid (mindless) patterns of device use, which may prevent them from interacting with their social environment. Technology may have positive effects to the extent that users feel in charge and able to use devices flexibly to support their aims.

The table below lists attitudes from SBI's study that contrast mindless and mindful use of mobile devices.

Table 1Mindless versus Mindful Device Use |

|

|---|---|

| Mindless Users Agree: | Mindful Users Agree: |

Source: SBI |

|

|

|

Survey respondents who showed mindless use of their smartphone showed more evidence of a self-imposed intervention to control their device use than did mindful users. For example, mindless users are significantly more likely to "spend a whole day without the internet or mobile devices," "turn off all 'push notifications' on their phone or other mobile device," and "turn off their mobile device to fully attend to an event or situation" than are mindful users. This counterintuitive finding reflects an important difference between mindless and mindful phone users: Mindful users appear to live comfortably with their smartphones, whereas mindless users appear to be battling them actively from time to time before falling back into old habits. Apps, accessories, devices, and business models that focus on deliberate disengagement from mobile devices would thus best aim at users who typically use these devices mindlessly.

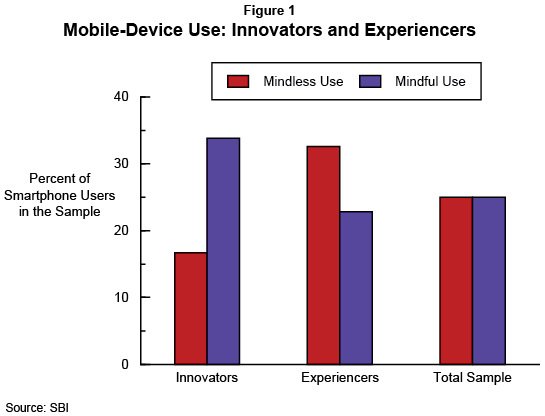

As Figure 1 shows, from SBI's VALS perspective, Innovators represent a consumer group that is more likely to show mindful use of mobile devices, whereas Experiencers show evidence of mindless, habitual use. The data show the top 25% of the distribution of mindful versus mindless mobile attitudes (equivalent to a "strongly agree" category on a four-point scale), and differences reflect deviations from this baseline. Innovators are curious, in-charge consumers who are able to balance the benefits and costs of mobile devices and use them to stay informed and productive. Experiencers are also curious—but impulsive consumers—vulnerable to extended, habitual device use, browsing, and interaction with friends through social media. Experiencers are likely to display elements of attention deficit in social situations and are generally more at risk of suffering the negative consequences of technology use.

To learn more about your mobile customers, contact the VALS team.